The Big Engine that Could, Did, and Continues to Make History

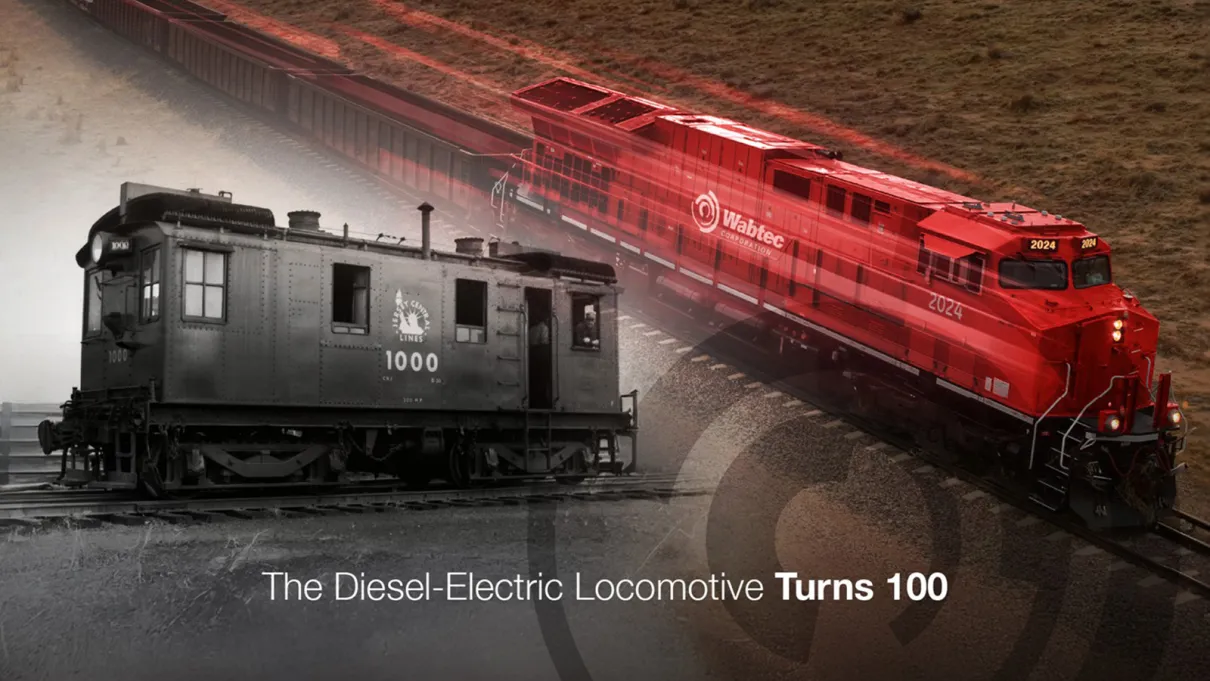

The diesel-electric locomotive turns 100, marking a century of innovation and performance

Introduction

On October 23, 1925, when the first ever diesel-electric locomotive rolled off the line bound for the Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ), its intended role in the “yard” was well understood, but its fate as a new type of engine was not.

Steam was king – and it had been for 100 years.

The thought that the diesel-electric engine, developed by General Electric in partnership with Ingersoll-Rand and the American Locomotive Company, would not only displace the steam locomotive, but also usher in its own 100 years of dominance, was not likely anticipated.

Except, perhaps, by Thomas Edison.

Edison had sensed electricity held possibilities steam could only dream of as early as the 1860s and began his pioneering work on all-electric trains later in Menlo Park, NJ in 1880. Yet it wasn’t until the emergence of Nicolaus Otto’s internal combustion engine (ICE; invented in 1876) as an industrial application in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – one that transformed the automotive, aviation, and shipping industries – that the idea of combining an ICE and electric propulsion system in a locomotive took hold.

The timing couldn’t have been more fortuitous. Steam had a problem. In fact, it had many. It relied on coal, which made it fundamentally dirty. It required manpower to shovel it from the tender into the locomotive firebox. And the only way to make steam-driven trains faster was to build larger and larger locomotives, which were in turn limited by rail infrastructure, as the entire system, not just the boiler, was forced to grow.

And even that wasn’t enough. In the parlance of our current century, steam had “scalability issues.”

It also had an image problem. The smoke and soot belching from coal-fired steam engines had drawn public scrutiny and triggered local regulations curbing such pollution within city limits.

A different kind of horsepower

“All of this – the pollution, the safety issues, the inability to scale to higher speeds and travel longer distances economically – led to a movement away from steam,” explains Kris Hoellen, Executive Director at the B&O Railroad Museum. “Most cities by that point had ordinances banning steam engines from entering their jurisdictions under their own power. That was true here in Baltimore, where the B&O Railroad would send out horses to meet and bring steam trains in. In fact, B&O maintained a large stable for this very purpose.”

Horses?! Edison saw an opportunity for step-change improvement, and in 1925, General Electric and its partners pounced. The diesel-electric engine was born.

“Edison had always been intent on offering railroads a cleaner, more economical alternative to steam,” says Steve Gerbracht, Director, Locomotive Architecture and Concept Development at Wabtec. “As the industrial uses of internal combustion engines took off, the light bulb literally turned on at GE that the locomotive, independent of catenary lines and third rails, could house its own power plant. Then, through the use of an alternator, the mechanical energy generated by the ICE – in this case a diesel engine – could be converted to electrical energy that could drive the traction motors on the trains wheels.

“This marriage of the internal combustion engine with Edison’s arsenal of electrical components and propulsion equipment literally changed locomotive history.”

From humble beginnings

The CNJ 1000 diesel-electric locomotive, also known as the “GE Demonstrator #9681,” wasn’t an overnight sensation, but it did get the job done – and did so more efficiently than its steam forebears.

The locomotive served in the Bronx terminal, near the port of New York, where it performed short-haul yard tasks such as breaking down and assembling freight trains, moving cars to different tracks, and connecting or disconnecting cars for other services, all while establishing a reputation for maneuverability and cost-effective operation.

Other railroads took notice.

Eager to investigate this new technology, railroads around the country soon ordered more of these “Box Cab Switcher” units and other experimental locomotives. The tide was slowly turning. Then came World War II, and the increased efficiency, flexibility, and lower operating costs of diesel-electric models proved irresistible. The die was cast – the diesel-electric era had begun.

The diesel-electric century is built on continuous improvement

“If 1925 represents the ‘aha moment’ of uniting the ICE with an electric propulsion system, the last 100 years have been about optimizing that package for greater performance, i.e., lower emissions and higher traction, horsepower, reliability, and fuel efficiency,” observes Bob Bremmer, Group Vice President of Product Development, Wabtec. “The success of this optimization journey, one Wabtec has often led, is a big reason the industry is celebrating this 100 year anniversary.”

While the list of innovations propelling the diesel-electric locomotive from “switcher” duty in the Bronx to the global heavy-haul behemoth it has become today is too long to enumerate here, Wabtec has played a key role in the most transformative milestones. These include pioneering the AC traction system, which boosted tractive effort by 60% over legacy DC systems; developing 4,500-6,000 horsepower engines (the original CNJ 1000 was 300 hp); and digital advancements in locomotive controls that have changed the paradigm of everything from trip optimization to remote diagnostics and support.

“What continues to amaze me,” shares Bremmer, “is that no matter how large or small the breakthrough we have made to coax more performance out of our locomotives, we’re still innovating on the diesel-electric platform established 100 years ago.

“Talk about staying power!”

A living legacy: looking forward, looking back

At the same time, there’s no denying that after 100 years of continuous – sometimes stunning, sometimes incremental – improvements to the diesel-electric locomotive, the performance curve is flattening. Yes, the diesel-electric engine is still king, and Wabtec still synonymous with making it run even better (for fresh evidence, see EVO Advantage), but Bremmer senses changes afoot.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the steam era lasted 100 years and diesel-electric the following 100. In fact, the challenges we face today in the rail industry in 2025 are quite analogous to those of 1925. Diesel-electric engines run really, really well, but there’s going to be a transition to other technologies in the future. We’re not quite there yet, but we’re at the beginning of a new chapter, the next chapter, one I believe will be as transformative to the rail industry as what occurred in 1925.”

However and whatever changes next manifest themselves in rail, the achievement of the diesel-electric engine can’t be overestimated. Its impact has been that broad, that transformative.

“I think the reason the diesel-electric locomotive has remained the go-to option for much of the world is the same today as it was when it caught on in the first place,” offers Chris Jackson, Senior Editor, Railway Gazette Group. “You’ve got that compact power pack with the flexibility to go anywhere.

“In the grand scheme of things, the diesel-electric locomotive has proven more efficient to operate than any other form of railroad traction: it can run longer distances and requires less maintenance so that it ultimately transports people and goods more efficiently than other modes. And that enables more economic activity to happen, and happen more efficiently. In the end, that has driven significant social benefits on top of payback to the railroads.”

Concludes Hoellen, “Across the U.S., there’s some 144,000 miles of freight track. I sometimes meet people, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, I don’t take the train,’ and I’ll counter that they may not, but just about everything else they touch and use does. Railroads facilitate over $2B in commerce per day in the U.S.

“And this all really came about because of the diesel-electric engine.”

Note: The CNJ 1000 is on display at the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore, MD. The museum is open seven days a week, 10 AM – 4 PM.